The best educated, most cultured and brilliant journalist in Italy talks about himself. Interview with Cesare Pillon.

In the preface to the “Manuale di Conversazione Vinicola” (Wine Conversation Manual), the editor-in-chief of the Corriere della Sera, Luciano Ferraro, described him as follows: “Pillon has been writing about wine since the 1970s and is the best educated, most cultured and brilliant journalist in Italy by far.” We interviewed him: he told us about his passion for gourmet food and wine, the origins of his career, the state of specialised journalism today.

Born in Turin in 1931 of parents from the Veneto, Cesare Pillon became a journalist at the age of 21: he began his career at the newspaper L’Unità, collaborating over the years with prestigious titles like the Corriere della Sera and Il Mondo. He covered crime, politics, economics, lifestyle and movie criticism. He has written many published works on the history of the Workers’ Movement.

From 1979 onwards, he focused on gourmet food and wine, penning numerous publications, and is the author of the historical-cultural entries in the Encyclopaedia of Wine published by Boroli; he took part in the Commission that made it possible for Christie’s to organise the first auction of Italian wines. He continues to write about wine and analyse the market in the daily Milano Finanza.

Cesare, you have stated: “I came into the world in 1931, one of the greatest vintages of the last century, especially for the reds. Clearly, wine was part of my genetic heritage, it was written in my stars.” After covering so many subjects for major newspapers, why did you decide to devote yourself to the world of wine?

Because I discovered that whoever makes a great wine, to whatever social class they belong, whatever their level of culture, they are never boring. You can make beautiful cars, for example, without having much of a personality but, to make a great wine, you have to be a great character. This is what fascinated me and made me decide that, as soon as possible, I would only concern myself with wine and gastronomy.

In your early career, up until the age of 48, you covered other subjects. Did this help you when it came to dealing with wine?

Absolutely, yes. Everything I covered, economics, health services failures… it all helped. There is no experience in my life that has not helped me, at the right moment, to better understand wine. My passion for chemistry as a youngster, my interest in history. The history of wine is one of the elements that attracted me the most. It’s part of the human story. You can’t understand human evolution without knowing how wine developed and the relationship between mankind and wine.

What was the work of a journalist like in the years you made your debut in the world of gourmet food and wine?

Newspapers were still composed with lead characters, they weren’t produced digitally. There was no Internet; the news did not come by teleprinters but still by fax. Interviews were done in person, not on the telephone or by sending questions and receiving answers by email. In short, the work was done in a much more direct way. More difficult, more complicated, longer, more effort. But certainly healthier.

What encounters were fundamental for your professional training?

A really important meeting was with Luigi Veronelli. I wrote about is some years ago, telling how it came about and why it changed my life.

I got to know him because I had to ask him to do an article on wine for Il Mondo; he couldn’t because he had an exclusive contract with Mondadori but he gave me all the help he could. Once published, he encouraged me, my publisher, Paolo Panerai, and all the winemakers he knew to help me continue on the path of gourmet food and wine.

When I met Gino, it was as if I had known him for years: I had always read everything he had written. I never managed to compile a proper archive of my publications, but I did with what he wrote. All his columns in Panorama, glued on strips of cardboard and properly listed. Seeing him in person seemed to me simply to be deepening an old acquaintance.

What did the opportunity to take part in creating the Encyclopaedia of Wine mean to you?

After 25, perhaps 30 years from my debut in the field of wine, it was an opportunity to take stock of all this experience. I realised at that moment that, by a stroke of luck, I had witnessed the renaissance of Italian wine because I had begun in the years when it had reached rock bottom. From that point, the only way was up. So it was, and here I am.

Is there some episode in your career that holds a special memory?

I remember very clearly one episode right at the start of my career in gourmet food and wine. I was making a survey of Montalcino when I met Count Costanti: he had all the traits that some years earlier I would have detested. He was a nobleman, an aristocrat, he had been a local party chief during the fascist period… And yet we got on so well I finally realised: labels are worthless, men must be judged as individuals. From that moment, I began to fight against intolerance. I had never been intolerant, but from then on I was certain that intolerance is truly the worst feeling that a man can have.

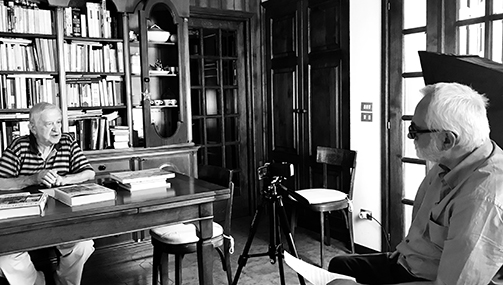

Cesare Pillon with Giacomo Bersanetti

You have written for many newspapers and publishing houses. How do you think the relationship between the press and journalism and the world of wine has changed and at what point do you think it is today?

I am very worried because there are symptoms of an attitude that is no longer healthy, no longer right, no longer tolerable. The truth is that there has been a democratisation, if you like, of the world of wine. The Internet now makes it possible for small companies to communicate directly with journalists; generally, they do it through public relations companies, which have multiplied out of all proportion.

Once, press releases were issued for really important event; they were sent by teleprinter or by post to specialist journalists, imposing an embargo in order not to disadvantage the last person to receive it. It was a complicated, long and costly business.

The Internet has made everything easy, and now I receive everything, including press releases asking for the publication of insignificant news in a questionable, if not offensive way. I find this deterioration very unpleasant.

At the end of the 1970s, when you began to cover gastronomy and oenology, these subjects were not “mainstream” as they are today. Do you think their wider dissemination is an advantage for the sector or do you think it is a case of overexposure? What does all this mean?

It is very true that there is overexposure. I had the good fortune to collaborate with newspapers edited by Panerai who was very sensitive to this issue and encouraged the publication of articles on wine at a time when this was very unusual.

But now, it’s all become too much. Everything comes down to the tasting: in 80 per cent of cases, communication focuses only on that.

I have always tried to tell the stories of the men of wine, the men who make the wine. I am convinced that the fundamental factor for great wines is the Cru, the selected vineyard, but the man who cultivates it is crucial. In my work as a journalist, and not only in the field of wine and food, I have always been convinced no one gets enthusiastic only about ideas. What interests them are stories about men. It is through the stories of men that ideas catch on. This is well understood by today’s populists, who deliberately use fear to get support for their ambitions.

How has the link between the world of wine and the world of finance changed since you wrote the first edition of the wine guide for executives in 1979?

We had drawn up this publication for a section of the economic weekly Il Mondo entitled “Personal Affairs” because it was intended for those managers, business people and readers who were personally interested in the subject.

Now everything has changed: there have been cases of wines sold en primeur, there are wine investment funds and, above all, there is interest now in investing in wine and therefore in auctions. I must say, however, that so far I am still the only Italian journalist who continuously reports on the auctions in Milano Finanza.

You have been a member of the Journalists’ Association for more than 50 years. Over this period of time, the profession of journalism has changed radically. What challenges do journalists in the sector face today?

Today’s journalists face major problems posed by the Internet, which is taking all the advertising. The successful outlets are the ones provided free to users via the Internet, but they are the slaves of advertising. This is not healthy.

The challenge that today’s journalists must overcome (and I don’t envy them) is not simple because, in reality, the phenomenon, like all human phenomena, has two sides: one is very positive, the democratisation of communication, the fact that everyone can take part. But there’s a negative side. And I must say that journalists are perhaps those with most to fear. The fact that copyright is not recognised (the attempt to ensure payment has already provoked a reaction from Trump, who argues that it is an attack on the very foundations of the United States) is really worrying.

Has the language of gourmet food and wine criticism in Italy changed over the years? In what way?

Yes, it has changed: the fact that everyone can take part has certainly lowered the level. We are a long way from the days when Gino Veronelli was involved, a man of boundless culture, or Mario Soldati, characters who wrote the most important literary works on wine. Currently, it has certainly all been dumbed down. But I think this is a transitory phenomenon. Any form of democratisation begins with a lowering of the general level before rising again.

Every year, you compare the scores of the main Italian guides, yet you say you “have never given ‘votes’ to wines”, and in the past you have expressed your agreement with Gualtiero Marchesi, when he disputed the “claim of giving an objective opinion expressed on the basis of personal taste”. What is your position on the scores given by the gourmet food and wine guides?

The gastronomic guides are not currently thriving, they are definitely in decline. They are no longer the consumer’s Bible and this, I must say, is a positive aspect of the advent of the Internet.

With regard to the question of the scores: I have tried to humanise them, comparing the scores of all the guides in order to obtain a collective consensus on one wine rather than another. But I have always considered giving scores to a wine a little arbitrary. A wine is appreciated for the emotions it can convey. And the emotions vary depending on the time, depending on who is tasting it, depending on what they are used to. It is too personal, in short. Certainly, there are great wines of indisputable importance for everyone, for whoever loves wine, and wines that are less important. But it is a long stretch to say that this one is worth 99 and this one is worth 97.5.

Carla & Cesare Pillon.

When you approach a wine, what are you looking for, what do you hope to find?

New emotions and unusual personalities are what strike me. The world of wine is very rich in this regard: truly extraordinary people, friendships that spring up around a bottle. It is difficult to establish such an intense relationship with a teetotaller.