Bottles and battles. The story of Guido Berlucchi told by the mind behind the success.

Franco Ziliani tells us about his professional experience in the world of wine, about the obstacles he has had to overcome along the way, and regales us with a few memorable anecdotes.

The company that he co-founded, Guido Berlucchi & C S.p.A., is market leader on the Italian market in the classic method sector, producing 4 million bottles a year and with around 10 thousand clients in Italy and in 33 countries around the world. The company currently has around 500 hectares of vineyards in Franciacorta and 90 collaborators working at the headquarters, in the cellars and on the vineyards. Since the harvest of 2014, the vineyards of the company now managed by Franco Ziliani’s children Cristina, Arturo and Paolo, are being converted to an organic regime.

Franco Ziliani with his children Cristina, Arturo and Paolo.

What intuition back in the 1950’s led you to create this company?

My career in wine officially started in the 1950’s, I was lucky enough to try Champagne. In those days we usually accompanied out panettone with Asti Spumante at Christmas, but my father worked in the wine sector (like his father before him), and one year he brought two bottles of Champagne home for the holidays. At that time I was studying enology in Alba, and I knew Champagne thanks to the great lessons of Professor Dell’Olio, who had a passion for the famous French wine. When I tried it, I decided that I would reproduce it in Italy. Naturally, first I would have to find a wine that could be suitable for refermentation in bottle, base of the classic method (at the time called méthode champenoise) which used to be taught by a very skilled technician. Often, to demonstrate the process, he would take us to the winery he directed, Calissano winery, in the centre of Alba. In Piedmont, like Cinzano and his “cellar of a million” (rumoured to contain a million bottles) they applied this method to Asti, at least until they moved on to charmat method, in other words on to fermentation in autoclaves..

In 1954, after resitting some exams, I got my diploma: I wasn’t a good student. I left Alba to return to the province of Brescia and soon after that my father passed away, so I closed his small company that sold wines popular at the time, and I started to cooperate as technical consultant for wineries, especially in the area of Lake Garda. One day Alessandro Borghese, a wine dealer, told me: “Mr. Berlucchi is looking for a technician: he wants to try to bottle the batch of Pinot Bianco he has at the castle.”

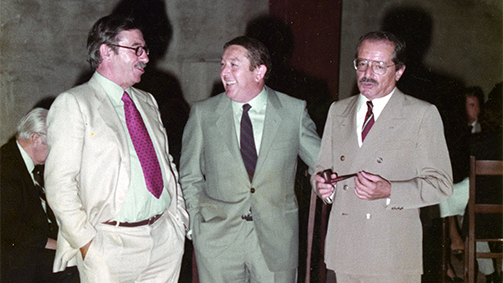

Giorgio Lanciani, Franco Ziliani and Guido Berlucchi.

So in 1955 I went to Palazzo Lana Berlucchi to meet the descendant of the counts Lana de’ Terzi. The house was incredible, and I was also impressed by the old cellar and the narrow alleyway that led to it: from a beautiful stairway you entered a vault, beneath which were some small cement bowls. It was in that cellar that, limited as we were by the strict laws, we began to experiment, bottling this wine, that Guido Berlucchi sold under the name of “Pinot del Castello di Borgonato”. He had designed the label himself and it depicted the lodge building in the passage of the 16th century residence; the wine was sold in Bordeaux-style bottles. Berlucchi loved Bordeaux.

On that day I put it to Berlucchi: “why don’t we do something a little more unusual? Let’s try to transform this Pinot Bianco with the champenoise method”. Guido Berlucchi was perplexed, but in the end he accepted. We created a company (at the time only verbally). Our goal was not easy to achieve: we didn’t have the right materials, we had no experience. The champenoise method was virtually unknown in our area, I had to make do. I often went to the enology school, but even my technician friends could only offer vague suggestions.

Three or four years went by, and in the meantime the wine in the bottles had started to ferment again, I never knew why. At a certain point, with the production of 1961, three thousand bottles came out well. I got some white wine to leave as brut and the following year some rosé too (that Guido named Max Rosé and which was the first rosé produced using the classic method in Italy, dedicated to his friend Max Imbert). The Pinot of Franciacorta was born. We put the bottles we had on sale: the new wine, after the initial scepticism, went down extremely well.

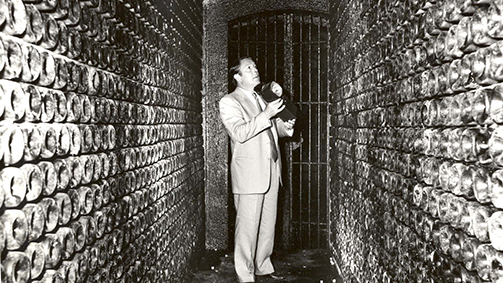

The Sixties: Franco Ziliani in the cellar and with the British Consul William Sharpe.

The next year we increased production, and still further in the years that followed. Demand started to increase, and to think that I started by dragging everyone I knew to the cellar to try it, friends, family. They loved it and bought crates of six bottles, then they would telephone and say they wanted another two, another five… Moral of the story: we started to sell out with ease. We went on for two or three years, continually increasing production. We were soon producing twenty thousand bottles a year. I remember when we stacked them in the cellar; myself, a butler of the Berlucchi household, Mr Guido’s personal butler (called Beppe), and the cellar manager. Laying down the last two bottles, poor Beppe exclaimed “well we’re ok for the next twenty years”, thinking of how long it had taken to stack away the first bottles: more than two years!

And how were those first bottles?

The first bottles came from the glassworks of Asti, they were beautiful, dark, with a pronounced, thin neck. The corks, which I bought from some producers in Piedmont, were cut from a single piece of wood. The cork was always a problem because occasionally, as you removed the wire cage, it would pop; other times it wouldn’t come out or broke, it was a hassle. Then there was another problem, we didn’t have a proper wine fridge, only a normal one, so freezing the liquid that was to be expelled took hours.

In the winter of ’62 I visited Champagne for the first time: it was the precise period when they were putting the crown corks in. I immediately adopted this technique too, but faced serious problems with the seal. The cork was a real obstacle.

Original packaging of Palazzo Lana.

At the beginning of the 1960’s I had abandoned my father’s company and opened a technical assistance office in Brescia, but I stopped by at Borgonato di Corte Franca in the morning and on my way back. One evening, in an office on the lower floors, I found some beautiful corks. They turned out to be some samples that a French visitor had brought from Spain. Without wasting a moment I had Mr Berlucchi lend me a car, an old Morris. I set off at once for this cork factory with a colleague who still remembers this trip. We set off at 6 in the evening and arrived at 11 the following morning. After a short stop at a motel, we loaded the car – inside and on the roof – with paper bags full of corks. I couldn’t wait to get back to use the new corks and replace the old ones, they were such a disaster. On the way down from Épernay in Borgogne, before turning off towards Mont Blanc, we hit a sudden storm. Back then it wasn’t motorway all the way. At a junction I had to brake hard: the corks on the roof were thrown all over the road.

We stopped the traffic, we threw the corks in the back of the car loose as the bags had fallen to pieces… when we set off again the car stank of cork, it was intolerable. We had to do the rest of the journey with the windows down. We got to the border at the foot of Mont Blanc at 5 in the morning: it was too early and the border wasn’t open yet. When they finally arrived and checked our documents they said: “here it says 24-25 parcels… all you have is corks!” The border officers thought it was a trick and started cutting the corks open to see if they contained something illegal. Only after I told them the whole story of the storm they let us go. By 4 in the afternoon we were back in the courtyard of the Palazzo. I said to the cellar manager “Battista, take the corks and put them in the boxes, I’m going to Brescia to sort things out with customs. When I got to Brescia I still couldn’t get the all clear. I tried to protest to an official, who replied “you tell me: you set off with 24 parcels, now you have 28, how come?”

Restyling of Cuvée Imperiale.

Can you describe the first packaging the bottles had?

The first packaging of our bottles was done in Brescia at Apollonio. It was conceived by the third partner, Giorgio Lanciani, who was passionate about art. The first label was beautiful but very expensive. It was oval shaped, with the name in relief. The shape made it stand out from the other wines. We wanted to be innovative, like producing sparkling wine in Brescia was. The year was shown in the centre of the label, which was also new, as at that time the year wasn’t normally shown on the bottle. But we had learnt a few things in France…

I’m sometimes accused by my colleagues of being a Francophile; actually I owe everything to France and its wine producers, like Moët et Chandon, who have hosted me dozens of times. I was always welcomed at Avenue de Champagne, in Épernay, by their PR person. It was the Countess de Maigret who, what a coincidence, had gone to college in Bologna with two sisters from Brescia. It was they who wrote us a presentation card the first time we went to Champagne. I’m not ashamed to say it, I copied everything I did from the French. From the crown cork to the first gyropalette, to the first dosing machines… We only needed the land. But I was determined to make a wine like Champagne. Because I asked myself: “is the quality of this wine simply down to nature or is a large part of it determined by the human factor?” I convinced myself that the human factor was the key, but in truth man can only preserve what nature provides.

Did the grapes you used to begin production come from the territory?

Our grapes came from Franciacorta. To begin with we used ours, also we bought them locally, sticking with Pinot Bianco. Pinot Nero didn’t exist. I planted our first Pinot Nero vines myself: it produced such small grapes, production was so low that cultivation of this variety only developed much later.

Original packaging of ‘61 Franciacorta and Cellarius.

Have you faced many difficulties in your career?

Particularly limiting laws and legislations have often posed obstacles that were difficult to overcome. For example, the chaptalization of wine that will be made spumante that is below the sugar level limit and therefore the alcohol limit. In France there is more freedom, and here it’s a problem. They were clever, they didn’t call it “sugaring” like in Italy, they named it after Chaptal who invented the practise.

Burocracy: a nightmare. I remember when to send wine to America I needed the INE stamp. I sent the documents, and in Rome they authorised shipping of the Pinot di Franciacorta, the Brut but not the Rosé. Why? Because the regulation stated that the wine must be “yellow with green reflections”. But if you let me use the Pinot Nero, why can’t I also make rosé? I had to fight to make it.

And that’s not all. We were the only producers in Italy that had to pay VAT raised to 38% for sparkling wines that had to be produced with fermentation in the bottle (méthode champenoise). The law had been introduced to target Champagne, but it also hit us as we used the same method. I went in person to Rome to knock on the door of the Ministry of Agriculture, and I didn’t let up until they changed the article of law.

I also remember falling out with the director of the consortium of typical local wines in our region, when I tried to encourage the producers, as few as they were, to plant Pinot Bianco and Chardonnay. One day he invited us all to a conference in which he argued that the wine of the Italians is quintessentially red. “No!” I exclaimed. Out of around a hundred people present, perhaps 98 of them sided with him. And so he stood up, raised a glass, of red wine, and proposed a toast: “I drink to the death of the sparkling wine of Franciacorta!” What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger…

2011, Brescia Teatro Grande: Franco Ziliani celebrated by the producers for his 80th birthday and the 50 years of Franciacorta.

Below: the limited edition dedicated to him.